“Panta Rhei”, meaning “everything flows” because, as the Greek philosopher Heraclitus said, “the only constant is change.” This also applies, perhaps today more than ever, to the world of wine, which is grappling with a rapidly shifting landscape of consumer attitudes and communication, and facing many challenges on which everyone has their own views. And so, in a space for dialogue and open debate, after the reflections of Angelo Gaja, one of Italy iconic wine producers, we welcome another contribution, gladly published here, from a producer who, we may say, “shapes opinion”, such as Martin Foradori Hofstätter, one of the leading figures of South Tyrol wine and, among other things, one of the first to seriously invest in no- and low-alcohol wines. These are one of the points in his piece, which also touches on themes such as communication, the value of terroir, the wine crisis, and more. Below are his words.

“The world of wine is not only old in its storytelling; no, the mindset of winemakers themselves is also outdated. We have become a fearful sector, like deer frozen in the middle of the road, blinded by the headlights of a car. The sector pretends not to see, preferring self-defense rather than taking on a proactive role which would allow us to find solutions capable, at least in part, of containing the drop in consumption. It almost seems that for every solution, we put a problem first. For years now, the wine industry has been telling itself that the decline in consumption will be offset by high-end wines, the so-called “cult” wines, those labels that - according to statistics - seem immune to the general downturn in sales. It is a convenient narrative. But also dangerously superficial. It is the narrative of a sector in deep difficulty, unable to renew itself, a sector that prefers licking its wounds rather than seriously addressing its problems.

Stop with the slogans like “wine must renew itself”, “wine must communicate with young people”. Stop with the words. The wine world needs actions and concreteness. Changing the regulations and lowering alcohol levels by one degree might be an idea. But enhancing one’s own territory could also be a partial solution. “Cult” wines are not arisen by decree or by the will of a marketing office. They arise when a wine becomes inseparable from the place where it arises, when that place stops being a backdrop and becomes the content. Just think of that small patch of vineyard in Burgundy, enclosed by a wall with a cross in front: inside, there are centuries of work, layers, memory. Not just wine, but identity. The rest is noise. Anyone today who believes Italian wine can be saved without seriously addressing the issue of true provenance is not creating strategy: they are buying time.

And, South Tyrol, which underwent an extraordinary qualitative revolution in the 1990s, now risks becoming more a guardian of the past than a builder of the future. Many recent initiatives were not arisen to strengthen the relationship between wine and territory, but to remedy “disorders” accumulated over the years. Even important tools like the Uga - championed, supported, and accompanied by me personally - carry compromises that I now consider outdated. Consumers today are far ahead of the sector that serves them. The restaurant world proves this: we no longer simply order a steak, we want to know where it comes from, what breed it is, where it grazed. In wine, however, we continue to confuse, multiply names, and hide behind brands and fanciful labels.

What makes a wine great? Quality, of course. But above all, its ability to express, year after year, the same place. That subtle, recognizable thread linking the glass to the vineyard. And when that vineyard becomes a destination of pilgrimage, then yes: we are dealing with a great wine. Without iconic vineyards, there is no wine tourism. And without these two levers, a territory becomes interchangeable with any other. This is precisely why I chose to push zoning work even further, vinifying single parcels and supporting this with an unprecedented geological study in South Tyrol. Not interpretations, not storytelling: scientific data narrating 250 million years of history and demonstrating how different, and not interchangeable the vineyards on the slopes of Mazon and Termeno truly are. For me, terroir is not a poetic concept: it is a measurable reality. Visitors want to “touch” vineyards. In Burgundy, for example, there is precise mapping of where each individual vineyard is located. The so-called “Grand Cru” vineyards have become true “pilgrimage sites”.

Now we arrive at a question: which came first, the chicken or the egg? Before reaching what happens in Burgundy, it will take more time. What distinguishes a “cult” vineyard from an ordinary one? Certainly, history and the recognition gained over time are essential. But regardless of this, consortia could become proactive by mapping not only Ugas but also creating useful tools for wine tourists. Then, even more importantly in South Tyrol case, they should revise the regulations governing the Ugas, since it is already clear that linking up to five varieties to each Uga only creates confusion and pleases only the skilled enologists who, to vinify their wines, need not a great solo grape but an entire choir.

The second answer to the crisis is the one the sector prefers to avoid: stop pretending that dealcoholized wines do not exist. Alcohol consumption is changing. That is a fact. Continuing to deny it is not defending wine culture but refusing reality. With the new regulations on dealcoholization in Italy, the market will inevitably be flooded with new products. The question is not if it will happen, but with what level of quality. The ideological rejection of dealcoholized wines is not a debate about quality: it is a collective defensive reaction from a shrinking sector. “I don’t like them, I don’t buy them, but people ask for them”, said a well-known sommelier. Exactly. The market asks, the sector looks the other way. Worse still: it pretends not to see that many products sold today as dealcoholized are actually flavored drinks made with juices, additives, and stabilizers. Consumers should be informed, even when they want an alcohol-free product. Reading the back label should become a cultural act, not a waste of time. Today, the wine sector prefers to get drunk on the status quo rather than look at the market with clarity. While consumption declines, analysis is replaced by ideology, and tradition is used as a shield against every change. I believe the exact opposite: more territory, but the real one; less hypocrisy, and more responsibility toward the future. Wine will not be saved by defending itself. It will be saved by choosing. And choices, by definition, do not please everyone”.

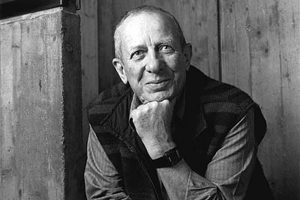

Martin Foradori Hofstätter

Copyright © 2000/2026

Contatti: info@winenews.it

Seguici anche su Twitter: @WineNewsIt

Seguici anche su Facebook: @winenewsit

Questo articolo è tratto dall'archivio di WineNews - Tutti i diritti riservati - Copyright © 2000/2026