What aesthetic model will be used in the future to judge wine? Will the current canons of quality by guide books and competitions continue to prevail or will the more evocative model linked to taste-olfactory values dominate? Can scientific research really measure these aspects with its tools? During a recent conference by the agricultural magazine “L’Informatore Agrario”, an update was given on the most recent steps made by scientific research and technology in the field of wine aromas.

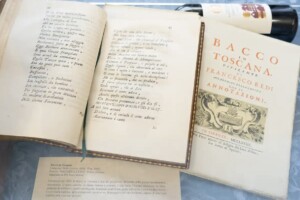

These include the genetic foundations of the synthesis of molecules of the physiology of the berry, varying the genetic and environmental conditions of grape vines and microclimates, as well as confronting the role of winemaking in technological and microbiological terms with numerous case studies. Below, the reflections of Professor Attilio Scienza, Viticulture studies, University of Milan: “It is difficult to imagine what the aromas of wine were like in the past: the meager descriptions that have reached us today of the organoleptic aromas rarely speak of the specific characteristics, primarily because the sense of smell was considered that closest to animal senses and brought man closer to beasts.

As well, the fleeting olfactory sensation makes it difficult to remember the sensations, even though since ancient times the nose has been considered the sense closest to the brain and, therefore, the origin of sentiments: the exquisite perfume of flowers “seems to exist only for man”, exclaimed Haller at the end of the 1700’s. Before the era of the chemistry of gases, a result of the combustion theories and experiments by Lavoisier, which defined air as a mix of gases that are the basis of its “quality”, the unpleasant odors that often polluted the air of cities signified disorganization and disorder, while pleasant perfumes were a fundamental vital principle, thus attributing a social role to odors. The smells of the rich were different from those of the poor. Aromas and perfumes were not only used as tools to improve tolerance levels against strong stenches, but also, naively, they were considered antidotes to illnesses like the plague, which was linked to unpleasant odors.

With this logic everything that was consumed became aromatized: wine, tobacco, foods, both sexual and spiritual experiences were all given olfactory endowments”. “The sense of smell is made up of a complex of diverse sensorial impressions, that is, the sense of taste, of temperature, and touch of the oral cavity, which contribute to making the forms of food”. This is the affirmation by Katz in his “Psychology of Form” written in 1948, in which he refutes the psycho-pharmaceutical, atomistic description of wine that really adds up to tactile, thermal, and sensorial sensations, and instead he considers the synergic effect of their parts which surpasses the sum of the same. Within the fruition of a wine the aesthetic behaviors are of normative or evocative character.

On the one hand, wine can be seen as a more or less perfect artifact according to the current canons of quality (guide books or points earned in competitions), which are actually represented by either the potency (concentration, body, structure) or elegance (finesse, delicacy, complexity). On the other hand, interior aspects can be looked for in wine, like soul and poetry. A most evocative image is comparing wine to a dance, its scents designing a movement. A great wine designs arabesques of perfume, is mobile, displays dynamic force, as confirmed by Dufrenne in his “Phenomenology of Aesthetic Experience”, written in 1953. With which of these models will wine be compared in the future? We hope it will be the second, that which Brentano in his “Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint”, loves as a friend, that is, not only in the sense that it is desired as something good which can be enjoyed with pleasure, but really is loved in the sense that we wish it well. Would we be able to achieve this solely with scientific research tools?

Attilio Scienza - University of Milan

Copyright © 2000/2026

Contatti: info@winenews.it

Seguici anche su Twitter: @WineNewsIt

Seguici anche su Facebook: @winenewsit

Questo articolo è tratto dall'archivio di WineNews - Tutti i diritti riservati - Copyright © 2000/2026