There is the “soft” wine, with its notes, aromas, and colors, which engages in dialogue with food and brings people together at the table, telling the story of the land, its history, culture, nature, and the community where it originates, and, then there is also the “rigid” wine, the one which attracts investments and acquisitions, linked to property valuations and the pricing of hectares and land. A wine which is measured not only in glasses but in financial returns, and which, as a strategic asset, also draws banks, insurance groups, and investment funds of various kinds (increasingly interested in the wine world, especially in recent years, ed). This is a topic often dealt by WineNews, and on which we gathered the reflections by Alessandro Profumo, one of Italy most prominent top managers, former head of banks such as Unicredit and Monte dei Paschi di Siena, as well as companies like Leonardo, and now at the helm of Rialto Venture Capital.

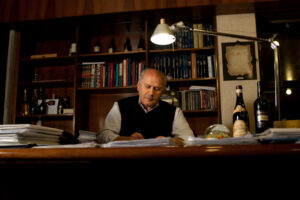

Alessandro Profumo explains why and how wine is indeed a strategic asset for Italy, and how the territory serves as the “keystone”, understood both as origin and uniqueness, as a “brand” synonymous with production quality and scenic beauty, but also as real estate value in business terms. So much so that, when asked what aspect he would analyze first if he was the manager of a wine company (his family already produces wine through the Mossi 1558 winery in the Colli Piacentini, headed by his son Marco Profumo, ed), the president of Rialto Venture Capital has no doubts: “the first thing I would analyze is the value of the territory - he says - because the value of wine is tied to the value of the land”.

It is no coincidence that, alongside historic companies investing in wine production across multiple regions, and private individuals entering the wine world and focusing on specific territories, from those with the highest vocation to emerging ones (Tuscany, Piedmont, and Puglia, for example, are in the sights of the world super-rich), financial and insurance groups have long been attracted by the value of land and wine as an asset: “it is partly marketing, partly business”, acknowledges Profumo, mentioning the example of Agricola San Felice, owned by the Allianz Group, which has invested in Tuscany three most prestigious wine territories: Chianti Classico, Montalcino, and Bolgheri. But, there are also Unipol Group Tenute del Cerro, spanning Nobile di Montepulciano, Brunello di Montalcino, Val di Cornia, and Sagrantino di Montefalco; Generali Le Tenute del Leone Alato, with estates in Veneto, Friuli-Venezia-Giulia, Piedmont, and Tuscany; and, internationally, Axa Millésimes of the Axa Group, with holdings in Bordeaux, Burgundy, Napa Valley, and more. Without forgetting banks, which, in addition to offering agribusiness services, have financed and developed partnerships over time with various Italian wine companies, from Feudi di San Gregorio to Terra Moretti, from Piccini 1882 to Terre Cevico, from Cirelli La Collina Biologica to Velenosi, just to name the latest case histories. There are also publicly listed companies, such as Italian Wine Brands and Masi Agricola.

“Wine is a business linked to the value of land and can represent a real estate investment”, continues Profumo. Because investing in wine doesn’t mean only monitoring Liv-Ex indexes and buying a bottle with the hope of future returns (in a market subject, like all, to fluctuations), but also investing in valuable real estate. And in the case of wine, “brick and mortar” means not only cellars but above all vineyards: according to the latest Crea data on land values, the most precious are those of Barolo, which can reach up to 2.3 million euros per hectare, followed by DOC areas around Lake Caldaro in South Tyrol (from 600,000 to 1.1 million euros per hectare) and DOC Bolgheri (from 250,000 to 1 million euros per hectare), which now matches the prices of Montalcino and its Brunello vineyards (one touches 1 million euros per hectare). For transactions in 2024, explains Crea, which is essentially stable, with a slight prevalence of demand over supply, and an average increase in agricultural land prices which was 1%, around 22,400 euros per hectare. “If we think about the value of a hectare of Sangiovese for producing Brunello di Montalcino compared to a hectare in Piacentino, the gap is staggering. It is clear that if these gaps narrow, significant returns can be achieved”, concludes Alessandro Profumo, who warns: “you need strong territorial marketing and a sense of community”, and above all, “produce good wine”.

Copyright © 2000/2026

Contatti: info@winenews.it

Seguici anche su Twitter: @WineNewsIt

Seguici anche su Facebook: @winenewsit

Questo articolo è tratto dall'archivio di WineNews - Tutti i diritti riservati - Copyright © 2000/2026