Inflation weighs on all sectors, and on the wine sector as well. If for many production sectors the most noticeable direct aggravation is that of energy costs, for wine production, as witnessed by many companies to WineNews in recent months, the increase in the cost of all “dry” raw materials (glass, paper, capsules, cages, cartons, corks and so on) weighs much more heavily than the energy cost. According to Unione Italiana Vini (Uiv), by the end of 2022, as a whole, the production chain will have incurred a cost increase of +83% over initial budgets, amounting to 1.5 billion euros in additional expenses. And, by 2023 an additional +20% increase is already planned for glass, among other things, on top of those already seen in 2022. Yet, in this overall scenario, as always, in a sector as fragmented as it is varied as the wine sector, which contains within it so many different business realities not only in size and turnover, but also in structuring (more or less capitalized, more commercial, with vineyards and not, and so on), and which sees different economic values not only between individual companies, but also between territories and regions, it is evident how some manage to absorb these costs better than others. With consequences for medium-term competitiveness that could go far beyond the immediate future. This is explained by the analysis, signed by the Divine Management Study Center of Studio Impresa, led by Luca Castagnetti, for WineNews, which started from the financial statements of 851 companies, which put together revenues of 12.9 billion euros, and focused on the key economic indicator for the success of a company, namely the “added value”, which is obtained by subtracting from revenues the components in purchases, from raw materials to services. From which it emerges, for example, that rising costs affect “strong” companies less, those that are more capitalized and have an almost complete supply chain, for which production costs generally affect the product less, than for “light” companies. But also that a “strong” company in a region such as Tuscany, for example, will have a significantly lower cost impact than a “light” one in Emilia Romagna.

“All wine companies are grappling with updating price lists for 2023. The issue has been turbulent since 2021”, Castagnetti explains, “and it has been approached differently from company to company: some have already made significant price increases in 2022 (+15%) and others have settled on smaller increases (3-5%). Distribution channels have also reacted differently: on the one hand, the large-scale retail trade has put up a very strong bar by declaring that it will not accept list revisions (and paradoxically it is the channel that has lost sales in 2022), on the other hand, other distribution channels both Italian and foreign have accepted increases that producers could not afford not to make. In this inflationary context, the market in the first 9 months of 2022 has, however, grown. We are now waiting for the fourth quarter data to have an accurate analysis of the overall market trend”. What can’t wait, however, is making an assessment of what the price lists will be for 2023, Studio Impresa explains, because the inflationary spiral seems to have no end: raw materials, glass, caps, cages, labels and cartons weigh down the bill of materials for bottles. Energy and services further erode the added value created. “As Studio Impresa’s Divine Management Study Center”, Castagnetti points out, “we developed analyses and simulations using our database on the balance sheets of 851 Italian wine companies. We looked at one specific indicator: the so-called “added value”.

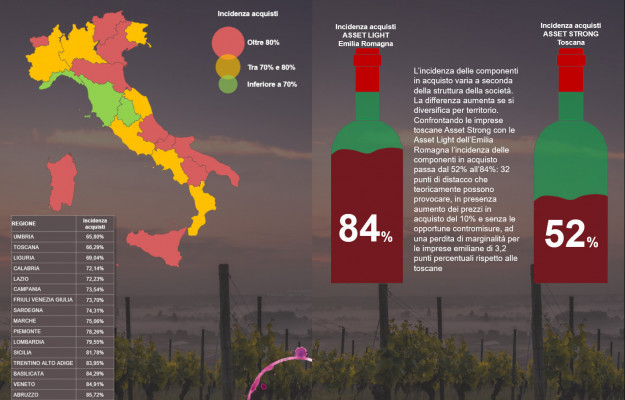

Technically, value added is obtained by subtracting components in purchases from revenues: from raw materials to services. These are the types of costs most immediately sensitive to inflation. Personnel and depreciation will definitely have increases, but they will manifest them later in time as these are costs with greater short-term rigidity”. The national distribution of firms, the analysis points out, is very diverse from region to region, and business models are very different. The national average incidence of components in purchasing is 81.29 percent. “But if we take an analysis of the main Regions by volume produced we find significant differences. We go from 66.29% in Tuscany, to 78.26% in Piedmont and 79.55% in Lombardy and then go up over 80% with Sicily at 81.78%, Trentino at 83.95%, Veneto at 84.91% and Emilia-Romagna at 86.04%”. And this starting difference, of course, leads to different consequences on the incidences of components in purchasing.

“A 10% increase in costs will affect only 66% of the costs present in the income statement in Tuscany and 86% in Emilia Romagna. This different situation”, Castagnetti further stresses, “could lead, in the absence of adequate countermeasures, to a loss of margins of two percentage points more in Emilia companies than in Tuscan companies. The main countermeasure is list price increases, but these present different difficulties from channel to channel. Large-scale distribution, for example, is resisting increases, and for Emilia-Romagna companies that had this as their main channel, 2023 looks like a very difficult year in making ends meet. So these companies will have to implement strategies to improve their productivity, implement economies of scale by growing in volume, and make investments in automation and digitization by improving work processes in the winery”. But, as mentioned, the differences are not only “regional”, but also between enterprise types. In the panorama of Italian wine enterprises, Studio Impresa in fact points out, there are two different business models: supply chain enterprises with vineyards and wineries, and more commercial enterprises with smaller investments. “We usually identify the former, calling them “strong” or supply chain, in those with an incidence of tangible assets greater than 30% of assets, and the latter, calling them “light”, in those with an incidence of less than 30%”, Castagnetti explains.

And, data from Studio Impresa show that the incidence of components in purchasing is 84% in “light” firms, compared to 76% for “strong” firms. The difference increases if we diversify by territory: “comparing the same regions as in the previous example, we find an incidence of components in purchasing of 52% in Tuscany versus 84% in Emilia Romagna: 32 points of detachment that would lead, in the case of a 10% increase in purchase prices and without the appropriate countermeasures, to a loss of marginality for Emilian companies of 3.2 percentage points compared to the Tuscans; Veneto - Castagnetti further elaborates - presents a situation similar to Emilia Romagna having an incidence of components in purchase of 84% for both “strong” and “light” companies. The approach to the 2023 list review, therefore, must take into account the business model of each individual company, and also be used to confirm and/or improve its market positioning. But, alongside the list review, other countermeasures related to productivity improvement must not be missing”, Castagnetti concludes, “which will have the advantage of remaining effective even in the future and desired return to the purchase prices of past years”.

Copyright © 2000/2026

Contatti: info@winenews.it

Seguici anche su Twitter: @WineNewsIt

Seguici anche su Facebook: @winenewsit

Questo articolo è tratto dall'archivio di WineNews - Tutti i diritti riservati - Copyright © 2000/2026