There’s a lot of talk about food fraud, but we need to fully understand the impact of this “ocean of crime”: this is the subject of the “Report on food crimes in Italy” organized by Coldiretti, Association of Italian Farmers and Eurispes, European Institute of Political, Economic, and Social Studies, to be presented today, with the collaboration, among others, of the anti-Mafia prosecutor, Piero Grasso; the President of the National Association of Magistrates, Luca Palamara, and the prosecutors Raffaele Guariniello, Anthony D’Amato and Vincenzo Macri.

The Eurispes-Coldiretti Report estimated that the total agro-mafia turnover is 12.5 billion euros (5.6% of the total): 3.7 billion euros from reinvestments in legal activities (30 % of the total) and 8.8 billion from illegal activities (70% of the total). The reinvestment of illicit proceeds from criminal activities in this sector results in conditioning free enterprise through fraudulent activity (such as, for example, fraudulent common market funding: in 2009 alone, the Guardia di Finanza, financial crime police, verified more than 92 million euros in fraudulent funding for agricultural subsidies); or through the implementation of extortion by imposing the hiring of recommended workers and, in some cases, forcing the industry to procure production equipment from companies close to criminal organizations, therefore influencing prices (through wholesale distribution management and transportation of agricultural products).

In the specific case of the Italian food industry, according to the Eurispes-Coldiretti report, the total added value (an average of 52.2 billion euros on an annual basis in the period 2005-2009) represents a strong incentive for criminal activities in terms of maximizing profit, investing proceeds from criminal activities in the sectors of agriculture: hunting and forestry (average added value 26.2 billion euros, 1.9% of the national economic system); the food sector, beverages and tobacco (average added value, 24.6 billion euros, 1.8% of the national economic system); fishing, fish farming and related services (average added value 1.4 billion euros, 0.1% of the national economic system).

The agro-food sector is less attractive in terms of investment profitability than other sectors with higher added value (real estate, construction, transportation, health care and social assistance), but is still appealing due to the persistence and, in some cases, aggravation of several critical factors (multiplier effect), such as a decrease of 15.9% in the number of workers and of 35.8% in real income per person employed in agriculture between 2000 and 2009; the significant drop in prices and production; the absolute prevalence of sole ownerships (87.2% of assets) in relation to partnerships and capital (respectively 8.9% and 2.4% of assets); the high incidence of small and medium-sized enterprises, often family-run, and the phenomenon of undeclared work. A primary “channel” of food crime is “Italian sounding”, that is, brand names that sound Italian but have nothing to do with Made in Italy products, with a global turnover of 60 billion euros a year: according to Coldiretti, “the spread and extent of the false Made in Italy phenomenon and the volume of business connected to unlawful conduct or improper business practices in the food industry are now of such magnitude that we can speak of the development of a real food mafia, whose growth and expansion are supported by the inadequacy of the control system and communication of data and information regarding imported food products as well as processing operations, distribution and sales”.

This all leads to the collapse of income and employment and to higher prices. Coldiretti has proposed an idea and a project to combat this state of affairs: the creation of an Italian food supply chain. It will be completely Italian as all procedures must take place in Italy, with Italian products strictly managed - at every stage whenever possible - mainly by the farmers; signature products because they are characterized by distinctive features of their places of origin and production that are immediately recognizable as a completely Italian product, with origin labeling, transparency of the sector and prices, and linked to their territory. In this way, a bond of trust will be built with consumers that would be able to restore Italian agriculture to a prominent role in the economic landscape and within the industry, with obvious economic benefits and a positive image, not only for agriculture, but for all the economic forces and trade operators involved or interested in the agro-food industry. Transparency and territorial links are essential for consumer confidence and to return the prominent role Italian agriculture deserves in Italy and abroad.

Then there is the aspect that goes beyond Italian sounding: agriculture and agro-food industry products for which indication of origin is not mandatory, making them impossible to trace. The list is long and includes pasta, cheese, UHT milk, pork, rabbit, sheep and goat meats, tomato-based products, processed fruits and vegetables, cereal derivatives. The lack of appropriate information and indication of origin on these consumer products (170 million kilos a year of mozzarella cheese), inevitably leads to the opportunity for all food industry businesses, driven by the need to reduce production costs, to decide to change their raw materials suppliers and contact primarily or exclusively foreign markets rather than the domestic one. There is also an economic (reduction of agricultural production, origin prices and the possibility of access to the network of supermarkets) and employment (businesses closing, layoffs, unemployment) risk for the entire Italian agricultural sector.

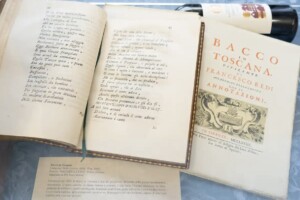

Not to mention the deception that consumers are victims of: they are unable to distinguish between a product of the Italian agricultural chain (real Made in Italy) and a product imported from abroad and end up making choices based solely on the consumer price. This problem affects the wine world, too: in 2010 Italy imported 32.219 tons of fresh or dried grapes (value of 53.9 million euros) from Turkey, Chile and Egypt (53.3%, 16.4% and 8.5% of the total), with an economic equivalent of imports in excess of 41 million euros (77.6% of total). In the same year, Italy imported about 62.375 tons of foreign wines made from fresh grapes, almost entirely from the U.S.A. and only marginally from Chile, Argentina and other countries. While imports of fresh and dried grapes are exclusively definitive, there are some marginal cases of wines made from fresh grapes of temporary imports and re-imports (4.9 tons and 300 kg in 2010). Regarding the province of destination of imported wines made from fresh grapes there is a significant concentration in terms of quantity 96.3% in the province of Cuneo, 89.1% in terms of economic value.

Copyright © 2000/2026

Contatti: info@winenews.it

Seguici anche su Twitter: @WineNewsIt

Seguici anche su Facebook: @winenewsit

Questo articolo è tratto dall'archivio di WineNews - Tutti i diritti riservati - Copyright © 2000/2026